THE TAGLINE

“The Black Prince of Shadows Stalks the Earth Again!”

THE PLOT

When last we saw the good Prince Mamuwalde, he had willingly accepted doom in the light of the rising sun rather than face an eternity without his bride. Sadly, Mamuwalde’s rest is short lived as the eeevil voodoo-Houngan wannabe Willis resurrects the vampire to use against his recently deceased mother’s followers after they wisely chose the beauteous Lisa as their new Mambo instead of him. Things don’t go as planned for Willis, however, as his would-be slave quickly becomes his master. Done with that annoyance, Mamuwalde turns his attention to investigating the circumstances which led to his resurrection, discovering in the process not only Lisa, but also an obscure voodoo ritual which she might be able to use to free him from the shackles of vampirism forever. Both frightened for her people and sympathetic to Mamuwalde’s plight, Lisa agrees to aid the prince by arranging the elaborate exorcism. Unfortunately, the ceremony is disrupted by a group of bumbling policeman led to the scene by Lisa’s worried boyfriend, an act which ignites Blacula’s blood rage. With her one opportunity to bring peace to Mamuwalde gone and the body count rising, the newbie priestess is left with no choice but to use her burgeoning talents to try and destroy the monster instead.

THE POINT

In 1992 one of the world’s most celebrated directors, fresh off of frightening the entire world with his daughter’s acting in The Godfather III, decided to continue on in the horror vein (pun intended) and released what was being touted as the most faithful adaptation of the novel Dracula ever put to film. Having just finished reading the book a second time, I was psyched, ready to see a Dracula movie which finally addressed not only the issue of Victorian sexuality (all the adaptations have managed to fit in the sex angle), but also touched on the subtexts of science versus religion and xenophobia, all the while telling a good adventure story with stalwart, heroic characters fighting a ruthless monster. So, yeah, it’s safe to say I hated Coppola’s movie right away. Don’t get me wrong, if you skip any comparison to the original book, the film has a few strengths of its own (visuals, Tom Waits) and has slowly grown on me over the years. A little. But with all the additions the film made to the story (really weird for Coppola, a director well known for slavishly sticking to his source materials), it’s not Bram Stoker’s Dracula. If it’s anything, it’s Francis Ford Coppola’s Blacula.

Go ahead, call me crazy. Again. (I’m pretty used to it by now.) But hear me out at least. In Coppola’s movie, a noble foreign prince cursed with eternal loneliness, chances across the reincarnation of his one true love. The prince becomes consumed with his desire to reunite with his beloved, but his unholy thirst forces him to occasionally transform into a demon and kill, an act which repels the person he so desperately longs to be with. Eventually the woman’s old soul reawakens and she overcomes her terror enough to see the man beneath the monster, but too much bloodshed has occurred and society demands retribution for his sins. Inevitably, the lovers are torn apart and, realizing his soulmate is forever beyond his reach, the prince willingly accepts death. Whew. Dramatic, huh? But the thing is, none of that stuff was actually in Bram Stoker’s novel. It was, however, the entire plot of the first Blacula movie. And when you throw in the fact that both movies contained some outlandish costuming choices (okay, so people in the 70s really wore the stuff you see in Blacula, but still) and both movies featured a powerful lead performance hamstrung by a ridiculous supporting cast, the only conclusion that can be reached is that Coppola didn’t give proper credit to the real inspiration for his movie. Ain’t that just like whitey? Can’t even give a brother his due!

Okay, okay, so odds are that Coppola didn’t really steal his love story angle from Blacula (that was probably just Oldman and Ryder making sure their parts got padded), but after recently sitting thorough a blaxploitation monsterthon (both Blacula films, Blackenstein, Abby a.k.a. The Blaxorcist, and The Thing With Two Heads) I’m not really in the frame of mind to give THE MAN the benefit of the doubt. (And technically, I am THE MAN!) So why have that reaction you might ask? Well, as Prof. Harry M Benshoff, writing in the Winter 2000 issue of Cinema Journal, explains things, blaxploitation horror films were those “made in the early 1970s that had some degree of African American input, not necessarily through the director but perhaps through a screenwriter, producer, and/or even an actor. The label “blaxploitation horror films” thus signifies a historically specific subgenre that potentially explores (rather than simply exploits) race or race consciousness as core structuring principles… Central to these films reappropriation of the monster as an empowering black figure is the softening, romanticizing, and even valorizing of the monster… a specifically black avenger who justifiably fights against the dominant order – which is often explicitly coded as racist.” So yeah, regardless of your own skin color, watch enough blaxploitation horror films and you’re likely to come away a bit suspicious of anybody who’s low on melanin.

Except it’s not quite that cut and dry with Scream Blacula Scream because, if you pay attention, you’ll notice there’s hardly any white people in the movie at all. Sure, there’s the obligatory bigoted white detective who is more than content to write off the slayings as just some crazy black voodoo types offing one another, but his character seems to be there simply because its a blaxploitation movie, which sort of requires that there be at least one obnoxious white guy in a position of power. Besides him, the only other non-black person of note in the movie is an early victim of Blacula played by 60s starlet Barabra Rhoades who says almost nothing and appears to serve little purpose beyond being eye candy. (And even that’s superfluous considering Pam Grier is in the movie. Oh, what? Like it was only black guys buying tickets to see Coffy?) With so few white faces in the film, the typical blaxploitation subtext of racial animosity doesn’t really take center stage in Scream Blacula Scream. But if that’s not what’s going on, then what is?

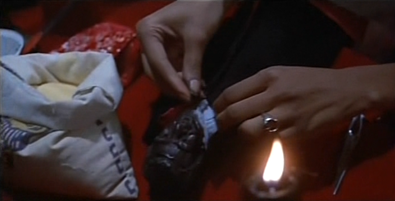

Well, to figure that out, you have to start with the character of Blacula himself. Prof. Benshoff proposes that, “In addition to suffering from racial discrimination from whites, Blacula is also an anomaly in the predominantly black community. While his skin color renders him the same, his noble African background positions him as the Other amongst contemporary black Americans.” And you do get to see this play out a number of times throughout the movie as Mamuwalde is confronted by the usual assortment of pimps, hustlers, and winos one finds scattered throughout blaxploitation flicks, encounters which always end with the prince sprouting his monstrous Blacula eyebrows and sideburns and laying waste to the offenders. The best such scene, for me at least, occurs when the newly vampirized Willis emerges into the parlor dressed in his finest polyester… um, I don’t know what it is (you look at the above picture and tell me) and strolls to the mirror to admire himself, only to learn to his utter dismay that nosferatu don’t cast reflections. Willis immediately begins shuckin' and jivin' Mamuwalde, trying his histrionic best to convince the prince of the importance of a man being able to see how good he looks before he goes out for the night. (Please, somebody who knows, tell me the costume designer didn’t really think that suit looked good and meant the whole thing as satire.) Mamuwalde will have none of it, of course, and gives Willis the verbal lashing he so richly deserves, if not for his bad taste in clothing, then at least for being such a narcissistic dodo.

But pimps, hustlers, and winos are not the only contemporary black Americans that Mamuwalde clashes with (thankfully, otherwise we’d be back in Stepin Fetchit territory); there’s also the members of Lisa’s congregation who all appear to be relatively normal (at least as normal as people dressed in 70s fashion can be). And it’s not Mamuwalde’s noble African background which causes friction with that group, but rather Blacula’s anger and rage, an attitude in direct contrast to their seeming contentment. In fact, it’s the low key personalities of the voodoo practitioners which brings about one of the consistent (and I believe unfair) criticisms of Scream Blacula Scream. There seems to be a lot of reviewers out there who believe that the character of Lisa is too reserved and timid to be played by Pam Grier. But I think that’s just pigeonholing an actress who has the range to properly play a role in the way it HAD to be acted. For instance, in what has to be the best scene of the movie in terms of atmospheric horror, Lisa, who has been sitting vigil over her best friend Gloria, stares in mute terror as the dead woman sits up in her coffin and beckons for Lisa to come to her. (Sadly for modern audiences, while the atmosphere remains, any true horror to be found in this scene goes completely out the window as soon as it becomes evident that the ghoulish Gloria is a dead ringer for a strung-out Whitney Houston.) Blacula bursts in to save Lisa, but his appearance and demeanor end up frightening her just as much, perhaps even more, than that of Gloria. The scene is pivotal in that it establishes the fact that while Lisa will agree to help Mamuwalde, she is fearful and wary of his bestial side and does not really see the vampire as a kindred spirit. This simply could not have been communicated as well had Ms. Grier gone all Foxy Brown, knocked out Gloria’s teeth, and punched Blacula in the groin.

Buried as it is beneath all of the usual B-movie horror trappings such as fakey looking fangs, badly animated vampire bats, and (where can I get one) Blacula voodoo dolls, this conflict between the various members of the black community is what provides the real subtext to Scream Blacula Scream. It’s pretty much accepted that Mamuwalde’s vampirism is an explicit metaphor for slavery what with his being symbolically shackled by Dracula and given the slave name of Blacula (Which never really made much sense as it is unlikely Dracula and Mamuwalde would have been speaking English. Still, I guess it can be overlooked since the Romanian word for black is negru and Negrula just doesn’t quite have that same ring to it.). And since his captivity is still in place as the 70s roll around, Blacula himself could be seen to represent the seething anger over the lingering effects of slavery and the ensuing years of discrimination following emancipation. This could go a long way towards explaining why Blacula never directly attacks the pimps, hustlers, and winos until they first assault him. From a blaxploitation perspective, these are the very same people most suffering from the same systemic evils as Mamuwalde himself, so he cuts them some slack until they cross the line.

It’s different with Lisa’s people, however. Even though the voodoo cult immediately welcomes Mamuwalde, it is on them the vampire begins to feed when his irresistible blood lust takes over. One possible explanation for this could be that, as Griffith University’s Dr. Amanda Howell points out, blaxploitation films often “focus on urban neighborhoods transformed into ghettoes by the widening economic gap between poor and middle class blacks and between blacks and whites”. According to Columbia University’s Amistad Digital Resources for Teaching, it was these “disparities between black city residents and those who lived in the affluent middle-class suburbs [which] finally produced a series of urban uprisings that drew their energy from the alienation and anger of the unfulfilled promise of equality under civil rights. While depicted as riots by the media and government, these uprisings very intentionally targeted the economic sources of oppression in their communities--department stores, downtown storefronts, etc.” In that context, it would be easy to read Blacula’s actions against the seemingly well-to-do voodooers as representative of those class-based inner-racial hostilities many poor urban blacks felt during that period.

But even if that’s what the filmmakers were getting at (assuming they actually were trying to get at anything beyond people’s wallets), Mamuwalde himself doesn’t see his own actions as righteous. Rather than use the systemic bigotry which brought about his condition as an excuse for his violent behavior, the prince instead wishes to be purged of his demons, which, in the context of the movie, can only come through Lisa’s religion. Until he can do that, Mamuwalde knows that he will never be the black avenger the ad campaigns claimed him to be, but instead just another monster who ultimately brings harm to the very people he is supposed to be avenging. In this self-awareness, Mamuwalde is actually drawing on the wisdom of that part of voodoo which comes from Christianity. If you don’t believe me, then ask modern day voodoo priestess Miriam Chamani. In an interview with the Christian Research Journal she admits that most of her followers retain some sort of residual Christianity in their hearts. “There was something instilled in us through those institutions that we cannot deny, and we found something [there] that made sense.”

And what makes sense in this case is the 1984 Instruction On Certain Aspects Of The "Theology Of Liberation" published by the Congregation For The Doctrine Of The Faith under the guidance of a guy you may have heard of named Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger. The document notes that “the acute need for radical reforms of the structures which conceal poverty and which are themselves forms of violence, should not let us lose sight of the fact that the source of injustice is in the hearts of men. Therefore it is only by making an appeal to the 'moral potential' of the person and to the constant need for interior conversion, that social change will be brought about which will be truly in the service of man. For it will only be in the measure that they collaborate freely in these necessary changes through their own initiative and in solidarity, that people, awakened to a sense of their responsibility, will grow in humanity.” Or, in essence, you can’t expect a twisted, broken system to be fixed by twisted, broken people.

Which raises some interesting speculations regarding Mamuwalde. Had not Lisa’s well meaning, but ultimately blundering, non-believer of a boyfriend interrupted the ceremony and denied the prince his salvation, what would Mamuwalde have done after the curse of Blacula had been lifted? (Assuming he didn’t crumble to dust that is, you know, what with his being a few centuries old and all that.) Some modern day black theologians worry that this is the point at which many people begin to do absolutely nothing. Anthony G. Reddie, writing in a 2007 issue of Black Theology (natch), worries that “by emphasizing the hyper-spiritualized nature of Christ’s saving work, White Christianity has been able to replace practice with rhetoric… In effect, Christian discipleship is reduced to those who are able to say the right words and identify with Jesus’ saving work; but with little accompanying need to follow his radical, counter-cultural actions. In short, White Evangelicalism has taught us all to “worship Christ” but not to “follow him.” Collective prophetic action has been replaced by private piety.”

While Mr. Reddie is primarily addressing a problem he perceives in certain protestant churches, it is one we all have to watch out for. Once we ourselves have been freed from whatever forces were enslaving us, the temptation is always there to get as far away from them as possible, leaving those still in chains to deal with the situation on their own. But as the 1984 Instruction points out, that kind of thing is a big no-no. “We are not talking here about abandoning an effective means of struggle on behalf of the poor for an ideal which has no practical effects. On the contrary, we are talking about freeing oneself from a delusion in order to base oneself squarely on the Gospel and its power of realization.” In short, we first find salvation for ourselves so that we may then properly bring it to the rest of the world. Or to paraphrase the old Funkadelic song, we free our minds so that our asses will follow.

THE STINGER

Having spent quite a bit of time with blaxploitation movies these last few weeks, I feel I must confess a small prejudice of my own. You want to know what I always hated about black people? I mean really, truly, not kidding at all, despised? The Jheri Curl. Now before you go sicking Blacula on me, please give me a minute to explain. You see, one of my closest friends in high school was black, so naturally, when it came time to head off to Atlanta to attend college, he was one of the guys who moved up with me to share an apartment. Which was great except for the fact that this was during the mid-80s, and nobody was bigger in the mid-80s than Michael Jackson. And Michael Jackson wore a Jheri Curl. That meant a lot of guys like my roommate decided to wear a Jheri Curl too. In all honesty, it wasn’t that big of a deal during high school, the only real annoyance being the occasional oily stain on the interior roof of my car. A bit of an ick factor, for sure, but nothing that couldn’t be handled. That first blustery January morning in Atlanta, however, when I was the second person into the shower, and my bare naked foot sunk into an ice cold puddle of thick, slimy curl activator… well, let’s just say I wasn’t attending church at the time and didn’t handle that so well. And thanks to class scheduling, I was almost ALWAYS the second person into the shower. Suffice to say, I learned to freakin’ hate the Jheri Curl. Still do. So if that earns me a visit from Dracula’s soul brother, so be it. Here I stand, I can do no other.

No comments:

Post a Comment