THE TAGLINE

“He Walks Through Walls Of Solid Steel And Stone... Into The 4th Dimension!”

THE PLOT

After burning down his own lab during an attempt to create a device which would allow the user to pass through solid matter, the brash and brilliant young scientist Tony Nelson shows up at his big brother Scott’s lab for help. The equally brilliant (yet not so brash) elder Nelson, who is in the process of perfecting a metal which is virtually impenetrable, happily hires on his sibling as an assistant. All seems to go well for awhile, but Scott’s mental stability begins to crumble after the credit for the super-metal Cargonite is all but stolen by his corporate sponsor and his fiancé Linda begins to have feelings for Tony. Consumed with bitterness, Scott breaks into his little brother’s locker and steals the younger scientist’s experiment in hopes of discrediting it. After all, there’s not much use in inventing an impenetrable metal if your brother invents a machine that can pass through it. Much to Scott’s shock however, his singularly unique brainwaves (an unfortunate side effect caused by the radiation from his own experiments) are the key to activating the machine, and he succeeds in developing the ability to to become intangible. Unfortunately, there is a terrible cost to his success. Scott quickly discovers that the energy required to change his physical state causes his body to rapidly age and the only way he can regenerate is to suck the life force from someone else, a process which proves immediately fatal for the victim. As Scott sinks deeper into madness and the bodies begin to pile up, it becomes apparent to Tony and Linda that they have to devise some method of stopping the man they both still care for. But how do you stop someone you can’t even touch?

THE POINT

Wow, who wrote this thing, Sigmund Freud? I mean, seriously, you’ve got a young studly scientist working on a device that can penetrate anything. And then you’ve got his older repressed scientist sibling whose invention involves the inability to be penetrated. Let me tell you, 4D Man is not so much a movie with implied subtext as it is a movie which hits you over the head with symbolism with all the subtlety of Wile E. Coyote getting a boulder dropped on his skull. Did I mention that Tony tests his penetrating machine by trying to thrust a long wooden pencil into an iron block? Exactly. One shudders to think what a director like Ken Russell would have done with this material.

Still, considering the director of 4D Man was Irvin S. Yeaworth Jr., it’s amazing the Freudian stuff made it onto the screen at all. According to Gary Westfahl’s Biographical Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Film, Yeaworth was “the son of an ordained minister (but never a minister himself, despite some accounts)… He first achieved a modicum of prominence in the 1950s as the head of a small Pennsylvania company, Valley Forge Films, producing noncommercial short subjects on religious themes; he had also by this time been credited as the producer and director of The Flaming Teen-Age (1956), an obscure teen exploitation movie with a devotional spin. One of his works must have been pretty impressive, for it inspired New York producer Jack H. Harris to invite Yeaworth to direct a cheap science fiction film for general release. In response to this odd opportunity, the devout Yeaworth surely prayed earnestly for divine guidance, and the Lord, once again displaying His infinite wisdom, advised him to accept the assignment.” That ‘cheap science fiction film’ turned out to be a little flick called The Blob, which immediately creeped and leaped its way into movie history and made a star out of its then unknown lead, Steve McQueen.

Having been pretty much guaranteed a chance to direct a second film due to the blockbuster success of The Blob, Yeaworth next turned to 4D Man, another cheap science fiction film based on ideas suggested by Jack H. Harris’ 13 year old son (um, the walking through walls and such, not all of that penetration subtext, at least I hope not). Unable to secure Steve McQueen for a second go around due to the actor’s rising price tag, the filmmakers instead turned to a couple of more then unknowns in Robert Lansing and Lee Meriwether. And again they struck gold. While former Miss America and future Catwoman Meriwether holds her own in what could have easily been a throwaway role as “the girl”, it’s Lansing who is the standout. He may be no McQueen, but he’s spot on in the role of the elder Nelson brother, both in the beginning when he’s all work and no play, and later on when he’s anything but a dull boy.

And it’s a good thing they chose some real actors, because cheap or not, the story kind of requires them. These characters aren’t your usual broadly played 1950s mad scientist types accidentally unleashing giant tarantulas and other such things on the world (not that there’s anything wrong with that, mind you). Instead, they’re more like real people who show up at the lab everyday to do some R&D in hopes of producing something useful whilst also finding a way to turn a profit for their bosses. (Sorry, folks, but only a miniscule percentage of real scientists are actively working on things which could turn us all into mutants. Darn it.) And unlike the happy go lucky teenagers of The Blob, these are flawed adults, sometimes admirable and sometimes a-holes. Tony is genial and genuinely concerned about his older brother’s feelings, having stolen a woman from him once before. But he’s also reckless (hey, how many labs have you burned down) and, let’s face it, not very resistant once Linda really starts coming on to him. And as for Linda, she’s intelligent and truly admires Scott, yet is pretty quick to throw herself at another man when he turns out to be a younger, hunkier, and, you know, more capable of penetrating things version of her betrothed.

But again, it’s Lansing as Scott who makes the movie. Like any good monster, he’s both sympathetic and frightening. You feel both his awkwardness and frustration in scenes like the one in which he comes upon his fiancé and brother sunbathing by a lake, and the pair immediately jump up and hurriedly begin putting clothes on over their bathing suits, almost as if Scott had stumbled upon them doing something else (which I’m pretty darn sure is just the association the movie wants you to make). But you also equally feel Scott’s creepy pent up lust and desire for control in scenes like the one in which he passes through the walls of Linda’s bedroom, gets mere inches from her face, and alternates between angry utterances and threats of a fatal kiss. Just the way he looks at Linda tells you he’s having major flashbacks to that experiment of thrusting a long wooden pencil into an iron block.

Which makes it sound like all 4D Man is about is the psychosexual undercurrent running throughout the narrative. But that’s not really the case. Kids can watch the movie and never notice any of that icky Freudian stuff. All they’ll see is a solid sci-fi outing about a guy who goes nuts and runs through (literally) the city taking what he wants and sucking the life out of people. And for grownups who’d prefer more palatable subtexts besides the main character’s sexual hang-ups to choose from, there are plenty of those as well. For instance, Scott’s condition can easily be seen as an allusion to the all-consuming bitter circle of drug addiction as he must kill to feed his power, but must evoke his power to kill, therefore using up more power and forcing him to find more people to kill. And in the conceit that it is only Scott’s unique brainwaves which can fully trigger the experiment, one could even find slight nods to Nietzche’s concept of will to power. Scott is the only one with the willpower to make the machine work, but it is a Nietzchean will, one that aims not at God or truth or absolute goodness, but rather one that is just a meaningless exercise to its own end. That being the case, it can ultimately lead to nothing but sorrow for all involved.

But probably the most interesting subtext which plays out in the movie is the paradoxical nature of the brother’s competing experiments. You see, for all intents and purposes, Scott is developing an immovable object while Tony is inventing an irresistible force. There’s even a line of dialog in the movie in which Scott recognizes this age old paradox and notes what a fitting allegory it is for the relationship between him and his brother. Which is kind of ironic, because as adherents to the scientific method, it’s most likely that both Scott and Tony would reject the whole notion of a true immovable object or irresistible force. That’s because the laws of physics would demand an immovable object to have infinite mass, which ain’t happening, while an irresistible force would require infinite energy, which ain’t possible.

Or is it? You see, the question of what happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object belongs more to the fancy of the philosopher rather than to the natural scientist’s study of observable phenomena. It’s the kind of self contradictory musing that goes all the way back to at least the 3rd century B.C. when the Chinese philosopher Han Feizi asked what would happen if a spear which could pierce all shields was used against a shield that could deflect all spears. A more entertaining version of the paradox comes from ancient Greek mythology in the form of the Teumessian fox, a giant beast that the gods decreed could never be caught. Tired of having the children of his city eaten by the creature, Creon of Thebes set loose the mystical dog Laelaps, whom the gods had blessed with the ability to catch anything it chased. Freaked out over the possible universal repercussions of such an impossible meeting, Zeus simply dodged the question and turned both animals to stone before they hooked up.

But ultimately, the only variation of the question to be of any real consequence is the one that’s come to be known as the omnipotence paradox, which basically asks, “Could an omnipotent God create a stone so heavy that He couldn’t lift it?” A number of atheists love this question because it would seem that either way you answer it, yes or no, you inevitably deny some aspect of God’s omnipotence. It’s a good enough question to have vexed a lot of people over the centuries, from Thomas Aquinas and Augustine, who both argued for certain understandings of omnipotence that differ from the one addressed by the question, to modern philosophers who speculate that there are different levels of omnipotence, to C. S. Lewis, who dismissed the asking of the question as utter nonsense to begin with. It’s all interesting, if sometimes convoluted, reading. And it may be a case of some people being too smart for their own good. Because, really, the simplest answer to the question might just be, “Yes, an omnipotent God could create a stone so heavy that He couldn’t lift it, because He already has.”

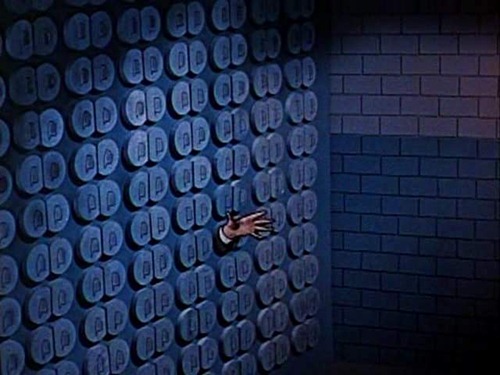

This solution is sort of hinted at in the finale of 4D Man (which I’m about to massively SPOIL), in which a mortally wounded Scott attempts to escape capture by passing through his own giant block of impenetrable metal, only to die halfway through. As film editor and movie critic Glenn Erickson observantly notes, “Since Scott's 4D existence is an unsustainable paradox, it is fitting that his godlike powers be neutralized by the collision of the two halves of his split personality: When the sexually charged 4D power stolen from Tony ("... When an irresistable force, such as you...") plunges back into the 'impenetrable' Cargonite that represents Scott's life-negating sterility ("... meets an old unmoveable object like me .."), the issue is resolved. Like Cronenberg's BrundleFly, Scott becomes one with his creation.” The final image we are given in 4D Man is of the irresistible force and immovable object becoming one and the same thing. And in a somewhat similar fashion, that is how God has answered the omnipotence paradox. Through the Incarnation, God became all at once a God who created the stone and a God who couldn’t lift it.

To accept this answer, of course, you have to accept the orthodox belief in who Jesus is as expressed in the Creed we say at every mass. Altogether now. “I believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible. I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God, born of the Father before all ages. God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father.” And yes, that’s the brand spanking new translation using the word consubstantial instead of the now defunct “one in being”. But as Russell Shaw explains, “The current translation to the contrary notwithstanding, “being” and “substance” aren’t the same thing. Being means “existence.” And while one trembles at the challenge of trying to say in a few words what “substance” means as a term in metaphysics, it signifies something like the unique, singular identity of a thing.” Or as the Catechism puts it, “The unique and altogether singular event of the Incarnation of the Son of God does not mean that Jesus Christ is part God and part man, nor does it imply that he is the result of a confused mixture of the divine and the human. He became truly man while remaining truly God. Jesus Christ is true God and true man.”

So God the Father made all of the stones, and God the Son can’t pick some of them up, even though they are in fact one and the same. (Yeah, yeah, I know Jesus gave us the beautiful symbolism of a faith that can move mountains, but nowhere does the New Testament describe Him juggling boulders in His spare time.) When you get right down to it, the answer to the omnipotence paradox, just like everything else… is Jesus. Who, now that I think about it, also had quite a bit to say about guys who spend too much time thinking about penetrating things. But that’s another post for another time.

THE STINGER

The Incarnation is just one of the many paradoxes we Christians contemplate all of the time. As Fr. John A. Hardon explained, “Christianity is the religion of paradox: that God should be human, that life comes from death, that achievement comes through failure, that folly is wisdom, that happiness is to mourn, that to find one must lose, and that the greatest are the smallest. What is paradoxical about the mysteries of the faith is that reason cannot fully penetrate their meaning, so that what seems contradictory to reason is profoundly true in terms of faith.”

No comments:

Post a Comment