ST. AUGUSTINE ON VENUS

A Guest Review by Xena Catolica

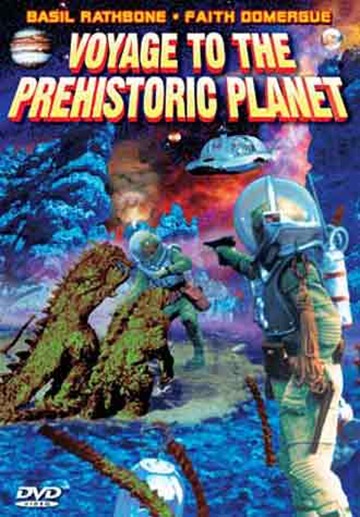

In the world of B-Movies, few films have suffered a weirder fate than the 1962 “Planet of Storms”, by the Leningrad Popular Science Film Studio. Filmed while the Soviet space program declined, it was swiped by American director Curtis Harrington, who added two characters, dubbed it into English, and falsified the Credits to hide his theft. The result: “Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet” in 1965, featuring Basil Rathbone and lizard men. He got away with it, and director Peter Bogdanovich then reworked the same film in 1968 to produce “Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women.” Only about ten minutes of added material are different, but in that ten minutes lies a world of difference, and that difference leads us to St. Augustine.

“Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet” tells the story of the first scouting mission to Venus, which fails. After the loss of their first ship to an asteroid, a team of astronauts and a robot land on Venus and quickly encounter a slew of rubber suits. After losing contact, another team flies out to rescue them, leaving Dr. Marsha Evans in charge of the ship and maintaining communications. The rescuers hear singing and one astronaut is especially taken with it. The robot starts to carry the two scientists across a lava stream, only to have its self-preservation program insist it jettison the passengers. The robot’s creator destroys the robot to save their lives. The teams meet but contact with Dr. Evens is lost.

Meanwhile, Dr. Evans decides it is her duty to attempt to rescue her “brother astronauts”, and she prepares to fly to Venus. They return to their rocket and make an emergency escape. The last scientist to board the rocket hears the singing again, and discovers a beautiful image of the ancient inhabitants. After the ship leaves, a robed figure like the carved image is shown reflected in a pool of water.

The moral universe of the movie is an attractive one. The scouts are genuinely curious and open-minded. They show mercy, console the sorrowing, and counsel the doubtful. They have scientific disagreements without huge egos, and a distinctly masculine sense of humor. When someone else is in danger, the language of piety creeps in, most especially when they hear Dr. Evans may be in danger—suddenly it’s “I pray” this and “I pray” that. And while the role of the female astronaut isn’t what we could hope for, in 1965 it’s nothing to sneeze at that she’s competent to run a large ship, take care of communications, and apparently fly a shuttle. Evans is brave and loyal, even if going to Venus alone is foolhardy. It’s a case of loyalty not governed by prudence, and her lack of prudence is offset by obedience to legitimate authority. Her appearance is feminine and professional. As a scientist and moral agent, she has more in common with Dejah Thoris than Lt. Uhura.

The reflected image of the alien is the most famous shot of the film. How many mysterious or disguised figures stand by water in life-changing events for travelers? Moses, Elijah, Raphael, John the Baptist, Christ, Philip the deacon…for a bunch of communist propagandists, the folks at the Leningrad Popular Science Film sure knew what messengers of revelation look like. The attraction of the astronaut to beauty can lead him to further beauty, to discovering a hidden truth.

The less said about the “Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women”, the better. In brief, Dr. Evans and her boss have been replaced by the Venus Swimsuit Edition. Enter the native women of Venus, psychic blondes who worship idols of murderous gods, who all have very prominent…cheekbones. When not praying for the destruction of the scientists, they pass the time knitting exciting undergarments out of seashells. References to praying by the scientists are cut, as is counseling the doubtful. The last sequence of the aliens shows them replace one hideous idol with another, ironically the robot who was sacrificed to save the same men they pray to be murdered.

Just in case anyone missed the pagan theme while admiring their cheekbones, the narrator at the beginning compares himself to Odysseus hearing the sirens and wishing to return to Venus. Somebody needs to reread their Homer, or at least watch the Dino de Laurentiis version, since Odysseus flees the sirens because they are Certain Death. He longs to return to his wife to defend his son from Certain Death. Should he return to Venus, our narrator would find himself in a nasty inversion of Odysseus’ actual return, as well as Certain Death. At the end, the attraction of the astronaut to beauty is a terrible danger.

And it’s a terrible movie. The director, who narrates, quit directing and went on to play Dr. Elliot Kupferberg in “The Sopranos”. Leave the movie, bring the cannoli.

So what has Venus to do with Hippo? These two movies illustrate the two responses to paganism by St. Augustine. The puzzle posed by paganism was that it was false, but its natural virtues, like loyalty, bravery, and respect for legitimate authority are the origin of rational morality in the West. As grace builds on nature, so faith perfects reason, and St. Augustine wasn’t about to let their natural virtue and reason go to waste. Instead, he emphasized the best in paganism and inviteded pagans to life in Christ by using reason. That’s response #1, and a short homily that illustrates it is here: (link to Sermon XCL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf106.vii.xciii.html )

The attraction of beauty and right use of reason (including the natural virtues as rational action) prepare the educated person for the revelation of Truth. That’s exactly what we see in “Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet” along with dinosaurs, carnivorous plants, and the Batmobile with antigrav.

Many pagans themselves had figured out that the gods of Greece and Rome were not worthy of worship by rational moral agents. Socrates, Euripides, and Ovid got in big trouble for saying so out loud. Remember the burning of incense to idols St. Polycarp got martyred over? The gods’ favor of Rome depended on worshipping them, so even if Zeus was a parricide and rapist, refusal to burn incense for the gods’ favor was treason because they would retaliate with plague, famine, and military defeat. It was still held by lots of pagans in St. Augustine’s day, who believed their continued worship of Zeus and pals was the only thing preventing disaster. So St. Augustine devised response #2, which was to demonstrate that the favor of the gods did not even exist! He began a history of all the pre-Christian disasters, showing that the gods had not prevented disasters even when they were widely worshipped. That much Certain Death got boring real quick, and Augustine delegated it to Bishop Orosius, hence it’s known as Orosius’ Seven Books of History Against the Pagans.

Response #2, demonstrating the futility and destructiveness of paganism is what we see in “Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women.” Idolatry is the failure of reason, as Augustine points out. And paganism without reason and virtue is ugly indeed. The attraction to beauty is made a life-threatening liability. It also deprives women of their dignity and moral agency. It’s still a rotten movie, but it’s not wrong, and the one moment of irony is distinctly religious.

Pagan gods keep popping up in the fiction of two prominent Catholic SF authors, John C. Wright and Gene Wolfe, and we have St. Augustine to thank for that. They are still gods unworthy of worship. But the virtues of paganism, and the fundamental goodness of human attraction to the good, the true, and the beautiful are strongly affirmed as an alternative to the violence, cowardice, and slavery of that idolatry we now call the Culture of Death. The Christian evangelist has at much at stake in the preservation of reason and natural virtue in America now as those Russian filmmakers did who snuck an angel past the censors in 1962.

No comments:

Post a Comment